A major driver of this growth is the weak rule of law in border regions. Provinces along the Thailand, China, and Laos frontiers suffer degraded governance, allowing well-resourced operators to construct and operate fortified compounds with little risk of law enforcement intervention. Neighboring states such as Thailand and Laos have also rarely intervened, prioritizing economic engagement with Chinese investors and cross-border trade flows over actions that could be construed as political interference in Myanmar’s internal affairs.

This has produced a regional posture of geopolitical passivity. Without coordinated, state-led intervention, these compounds continue to operate as transnational criminal sanctuaries that undermine global counter-fraud systems. Domestically, militias and junta-aligned forces have exploited governance gaps to extract revenue from these scam centers, ensuring they remain vital economic lifelines for local armed actors. As long as these criminal economies are protected by both local and regional power brokers, global financial institutions face elevated exposure to laundered proceeds, synthetic identities, and fraud-enabled payment flows.

Criminal ecosystems: Transnational networks

Another critical dimension of Myanmar’s cyber scam industry is its linkage to Chinese organized crime syndicates. Evidence from regional investigations, including by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), has tied the management of compounds and the online payment channels they support to established criminal syndicates with decades of experience in money laundering, trafficking, and illicit finance. Their involvement ensures that scam compounds are not isolated local enterprises but nodes in a broader criminal economy spanning mainland China, Hong Kong, and Southeast Asia.

The fusion of organized crime with local militias and business elites has entrenched scam operations as durable economic ecosystems rather than temporary criminal ventures. These operations are sustained by sophisticated cross-border logistics networks. Victims trafficked into compounds often report being passed through multiple hands — from online recruiters, transport agents, and local fixers before arriving at scam centers. Brokers and facilitators not only manage the recruitment and trafficking of scam center workers but also procure critical operational assets such as telecommunications infrastructure. These logistics pipelines reveal a high degree of coordination and planning.

Case study: Dongmei Park and Wan Kuok Koi

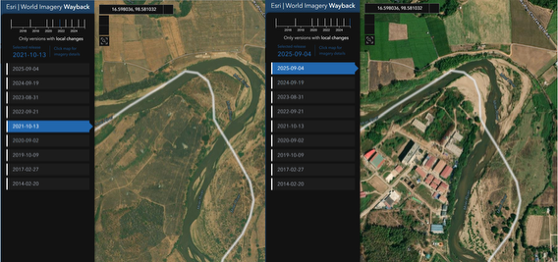

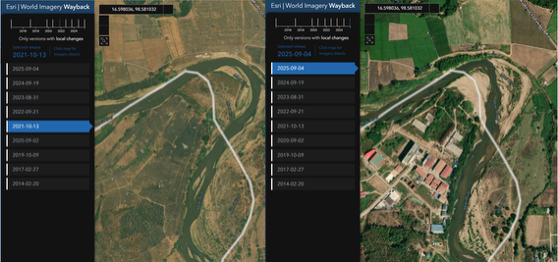

The Dongmei Investment Group Co., Limited financed the construction of the Dongmei Park scam compound in Myawaddy, Myanmar (16.598036, 98.581032).

Survivor accounts and public reporting identify the site as a hub for large-scale pig butchering scams. The Australian Federal Police (AFP) describe pig butchering as scammers building fake trust with victims before luring them into fraudulent investments or other financial traps. These schemes are estimated to have extracted $75 billion (USD) globally from victims between 2020 and 2024. Although Dongmei Park was marketed as a cross-border investment zone, corporate registry checks in Hong Kong and Malaysia, along with financial filings, reveal largely dormant commercial activity — wholly inconsistent with legitimate projects of this scale.

At the 2020 groundbreaking ceremony for Dongmei Park, Wan Kuok Koi (also known as “Broken Tooth”) appeared alongside Malaysian investors. According to a WeChat post by an organization affiliated with Wan Kuok Koi, he attended in his capacity as chairman of the Dongmei Group Board of Directors. Previously linked to a Macau-based criminal syndicate, Wan Kuok Koi also held a leadership role in the World Hongmen Historical and Cultural Association.

OSINT analysis of YouTube footage, UNODC reporting, and financial data indicates that Wan Kuok Koi also became involved in shadow banking. In 2018, he launched the Hong Coin cryptocurrency in Cambodia, Thailand, and the Philippines. Approximately 450 million tokens were sold, raising $750 million (USD) through World Hongmen Investment in partnership with the All In Group. Subsequent trading patterns displayed “pump and dump” characteristics, suggesting the cryptocurrency was used for money laundering and investor fraud.

Wan Kuok Koi has been sanctioned by the U.S. government for money laundering and involvement in human trafficking linked to Dongmei Park. Despite these measures, he remains active. In August 2025, he announced plans to invest in Web3 and a global digital trust network. Chinese-language OSINT placed him in Laos around the same time, inspecting an entertainment complex, pointing to continued expansion of scam compound-linked ventures across the region.

Although a visible public figure, Wan Kuok Koi represents only one node in a wider criminal economy spanning multiple scam compounds across Myanmar. Archived photographs and Chinese-language OSINT link him to the Bai family of Kokang, one of the so-called Four Great Families that dominate Myanmar’s gray and black markets.

Bai Yingxiang, daughter of Kokang leader Bai Suocheng, has been accused of concealing her family’s role in telecommunications fraud, money laundering, and human trafficking centered on the Tiger Villa compound — another site implicated in scam trafficking operations.

In parallel, cryptocurrency tracing investigations have connected the KK Park compound to Wang Yi Cheng, vice president of the Thai-Asia Trade Association. Like Tiger Villa and Dongmei Park, KK Park has been linked to both human trafficking and pig butchering scams. Notably, Thai-Asia operates from the same building as the Overseas Hongmen Culture Exchange Centre, strengthening suspected network linkages between KK Park, Wan Kuok Koi, and broader Hongmen-affiliated financial channels.

The case of Dongmei Park illustrates how illicit financial ecosystems underpin the physical and operational expansion of Myanmar’s scam compounds. Marketed as legitimate cross-border investment, the site has been identified as a nexus of transnational organized crime, blending corporate facades, militia protection, and shadow banking. Left unchecked, such compounds erode financial integrity, destabilize regional markets, and expose global economies to systemic risks.

Financial infrastructure: The shadow banking backbone

As demonstrated in the case study above, the persistence of Myanmar’s scam compounds is not sustained solely by coordinated human networks but by a parallel financial architecture that underwrites operations. At the center of this architecture is a shadow banking ecosystem that provides liquidity, transaction anonymity, and laundering capacity. This infrastructure is more than an enabling mechanism. It is a structural pillar of the scam economy, insulating illicit actors from regulatory disruption and enabling them to scale operations across borders.

A critical inflection point occurred in 2021, when China and Myanmar began settling bilateral trade in yuan to bypass SWIFT restrictions imposed by Western sanctions. While this policy reduced transaction costs and accelerated cross-border settlements, it also shifted Myanmar’s financial flows into oversight regimes with weaker external scrutiny. The outcome was twofold: Bilateral trade was insulated from sanctions pressure, but illicit actors were simultaneously afforded greater opportunities to conceal criminal transactions within ostensibly legitimate commerce.

This structural shift coincided with the rapid expansion of regional e-commerce and fintech platforms, further reducing transparency in cross-border payments. These digital channels have created blind spots in anti-money-laundering (AML) monitoring, which scammers exploit by routing victim funds through yuan-denominated on-ramps, stablecoins, and decentralized finance (DeFi) services linked to Chinese marketplaces.

Two prominent examples of this shadow banking system are Xinbi and Huione. Both replicate the functions of regulated financial institutions, offering payments, remittances, investment-style returns, and cryptocurrency conversion services. Yet they operate entirely outside formal regulatory frameworks. For scam operators, these platforms are indispensable. They provide cross-border liquidity, reduce reliance on banks subject to compliance monitoring, and ensure operational redundancy through multiple parallel transaction channels.

Case study: The Xinbi banking system

Xinbi is an example of the financial infrastructure underpinning cyber scam operations. The platform markets itself as an online payment service through its website, Xinbi.com, which links directly to multiple Telegram accounts, including @xbdb, a channel with more than 111,000 members.

Content posted in these channels shows that Xinbi functions as a marketplace for illicit financial services and instruments. Advertisements promote mule accounts, e-wallets, and QR code-based laundering infrastructure, fast-track money movement channels (“Direct Train”), mechanisms of trust enforcement between criminal actors (“Double Guarantee”), and recruitment pipelines for mules and low-level operatives.

Open-source tools, including domain lookups, indicate that Xinbi.com is associated a gmail address linked to several social media profiles, including accounts on X (formerly Twitter), YouTube, GitHub, Facebook, and LinkedIn — all affiliated with a U.S.-based software engineer. This suggests Xinbi’s branding and digital presence may have been seeded, at least initially, by individuals presenting as legitimate technology professionals.

Corporate registration records provide additional insights. Documentation shows that a company named Xinbi Co. Ltd. was incorporated in Colorado in 2022, with an address at in Aurora. While it is unclear whether this entity is directly tied to Xinbi’s illicit marketplace or simply used as a front, its existence demonstrates how scam-linked services can acquire a veneer of legitimacy by embedding themselves in reputable jurisdictions.

This case illustrates the value of OSINT in mapping the digital and organizational footprint of entities that sustain scam economies. With nothing more than publicly accessible domain records, Telegram monitoring, and corporate registry checks, investigators can trace Xinbi’s role in laundering victim funds and supporting the wider cyber fraud ecosystem in Myanmar.

Case study: The Huione banking system

The organization Huione, accessible via its website huione.org, markets itself as a provider of online payment services, including blockchain infrastructure development, token-based ownership models, and high-throughput transaction processing. Like Xinbi, Huione operates its own Telegram channel (@Huione_OfficialGroup) where users, vendors, and service providers engage and transact.

OSINT methods, including free and publicly available corporate data repositories, reveal that Huione is not a single entity but a sprawling web of interlinked companies. Its structure spans multiple jurisdictions, including:

- A currency exchange, payment service, and insurance firm in Cambodia

- A software engineering company in Canada

- A cryptocurrency firm in Poland

- A liquidation business in Switzerland

- A global holding company registered in Colorado, U.S.

This jurisdictional diversification gives Huione resilience. Each country applies different licensing regimes, enforcement priorities, and anti-money-laundering/counter-terrorist-financing (AML/CTF) standards. By distributing enterprise functions across borders, Huione makes it difficult for any single jurisdiction to disable its operations.

Furthermore, Huione’s integration with legitimate remittance and payment services blurs the boundary between lawful and illicit capital flows. By embedding itself within standard payment regimes and processes, Huione makes illicit transactions harder to isolate and disrupt without collateral impact on legitimate users. This blending of services is a hallmark of the shadow banking systems underpinning scam operations across Myanmar’s border regions.

Taken together, these case studies illustrate the critical role of OSINT in unraveling complex, multi-jurisdictional financial structures. By combining corporate registry queries, blockchain tracing, and social media analysis of both Western and Chinese-language platforms, investigators can expose how scam compounds in Myanmar sustain themselves through sophisticated global payment networks.

Conclusion: Implications for financial systems and policy

Myanmar’s cyber scam compounds are not isolated criminal enclaves but part of a transnational trafficking and financial ecosystem. These operations exploit weak governance, organized crime linkages, and parallel financial systems that mimic legitimate banking. Platforms such as Xinbi and Huione show how easily illicit actors leverage cross-border corporate structures and remittance channels to launder billions while maintaining resilience against disruption.

For banks and financial institutions, this underscores the need to:

- Enhance due diligence on fintech platforms, remittance services, and cross-border payment networks operating in high-risk jurisdictions

- Invest in OSINT capabilities to complement transaction monitoring, enabling proactive identification of illicit actors and networks

- Strengthen collaboration with blockchain analytics providers to trace illicit flows across fiat and crypto rails

For policymakers and regulators, the priority is to:

- Close gaps in AML/CTF oversight by targeting shadow banking systems that straddle multiple jurisdictions

- Improve cross-border legal cooperation to prevent criminals from exploiting enforcement asymmetries

- Support OSINT-led investigations through capacity building, resourcing, and policy frameworks that legitimize its use in financial intelligence

A response to this shadow banking ecosystem requires collective action. These scam compounds are not merely a regional crime challenge but a direct threat to the integrity of global financial systems. By integrating OSINT into the compliance and enforcement response, the financial services community can play a decisive role in disrupting these networks, safeguarding victims, and defending the resilience of the global financial system.

Emerald Sage is the principal intelligence advisor at OSINT Combine, a global leader in open-source intelligence (OSINT). Sage and the OSINT Combine team bring together expertise from military, intelligence, law enforcement, technology, and business sectors to deliver the software platform NexusXplore, which offers comprehensive training programs that empower teams and mission-specific datasets.

To read Sage’s complete report on Myanmar scam compounds, click here.