Everyone knows it is best to tackle a problem at the source. In the world of cybercrime, this is an accepted fact. Stop the mules, stop the fraud. It sounds like an easy solution, yet the traditional ways of tackling the issue continue to fail across the industry as most banks focus so much on transaction monitoring to detect money laundering. It is like mopping with the tap wide open, but everybody still seems to be happy with it.

The current situation for addressing money laundering is costly. Banks and financial institutions already have extensive AML/CTF programs in place, including Customer Due Diligence (CDD) and Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD) at onboarding and screening customers against long lists of PEPs and sanctioned people. When customers have become active, there is Ongoing CDD, like transaction monitoring.

Then, there are the large teams in place to support these processes (in larger banks, especially in Europe, there are often thousands of people handling all this). These teams are often working with transaction monitoring that relies on old rule-based systems leading to high false positives that keep these teams at work. The final result is current AML processes are generating huge operational costs.

Unfortunately, the first malicious transaction in a mule account typically isn’t detected correctly. Either the system oversees it, or it is alerted as possible fraud but the customer confirms it as genuine (of course!), or the AML analyst classifies it as not-suspicious, or the money launderer comes up with a plausible explanation. The more transactions that occur, the more extensive the investigation and the more reporting required to the FIU. Also, there is the risk of regulatory fines that might be imposed if AML monitoring is determined to be inadequate.

Transaction monitoring is reactive by definition. The moment a transaction is executed, you are already a step behind. It is like driving on the highway by looking in the rear-view mirror, completely missing the turn you needed to take. You need a transaction to act upon, and typically you will have at least a few. So, you know transaction monitoring isn’t perfect, yet the huge regulatory fines leave you no other option. Or is there?

The Forgotten Gap: Detect Money Launderers Before They Transact

We know that what we are doing today is not working, and it is logical to want to improve transaction monitoring by optimizing what we have and know best. Can we use more advanced controls, scenarios, and rules to lower false positives? Can we use machine learning to assist analysts in making the right decision when handling alerts, and do this faster? These are good and valid thoughts, but it is like buying a golden broom. Even a perfect transaction monitoring system will always detect money laundering by the first transaction leaving us stuck in a reactive cycle.

The other option is to shift to looking at account opening. CDD is becoming more scrutinized and EDD is executed more often, leading to increased friction and a lowered genuine customer conversion rate. Yet, it is obviously not effective as we still suffer from money laundering. Criminals are clearly able to get through.

This is where we need to consider new ideas to solve the problem, and I see the detection opportunity in what I call the forgotten gap – the time between account opening and the first transaction (see figure below).

Money launderers carefully nurture their accounts. They are “matured” like good wine. The older the account is, the better, or in this case, the more trustworthy. Additional accounts are acquired from unwitting mules where criminals use legitimate businesses and convince unknowing victims to participate. From time to time, the account is checked to ensure it is still open and functioning. Before actually being used, the account is handed over to the money launderer.

Money launderers carefully nurture their accounts. They are “matured” like good wine. The older the account is, the better, or in this case, the more trustworthy. Additional accounts are acquired from unwitting mules where criminals use legitimate businesses and convince unknowing victims to participate. From time to time, the account is checked to ensure it is still open and functioning. Before actually being used, the account is handed over to the money launderer.

These are only some examples of behaviour that can be detected in online channels. Money launderers - and criminals in general - behave distinctively different from genuine customers. Using behavioural detection is highly effective and we have the numbers to prove it.

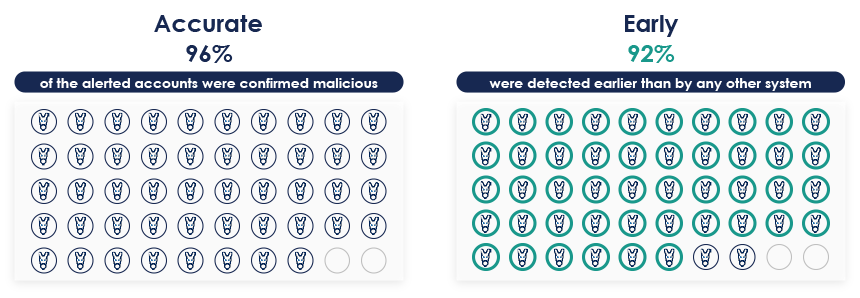

Several large international banks are using behavioural biometrics to find mule accounts pro-actively: before they transact. The number of mule accounts detected differ per bank, but in some cases, we have seen up to 1,000 per month and with an extremely high 96% accuracy rate. In addition, we have found that behavioural biometrics is detecting mule accounts in 92% of the cases before traditional AML and transaction monitoring systems alert the bank.

Remove the Means, Remove the Problem

Remove the Means, Remove the Problem

Without accounts, money laundering is impossible. A large Australian bank noticed this when they started hunting down money mules, using behavioural detection methods in their online channels. Eliminating mule accounts early helped the bank reduce fraud levels by 70%.

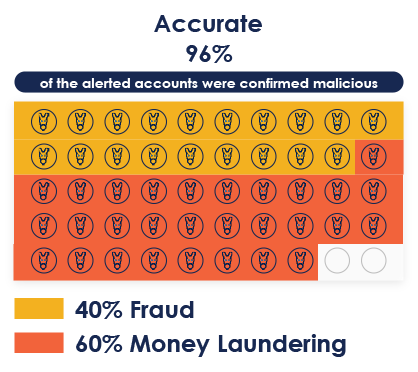

Your next question might be, “That’s fraud and money mules, what does that have to do with money laundering?” Well, there is not an easy answer to that question, and the only way to answer it is if the high-risk accounts are kept open so that we can have the opportunity to see what they are up to. BioCatch data shows that 40% are used for cashing out and moving money derived from online banking fraud. The other 60% are used for money laundering, the usual placement, layering and integration. This raises a question: could it be that the accounts harvested later are sold to fraudsters or money launderers? That their destiny is not decided at birth, but later in life? Or is it that both fraudsters and money launderers have the same level of professionalism and experience that makes their behaviour differ from genuine customers and therefore detectable? Regardless of the story behind it, the data shows one thing clearly. As an industry, we are dealing with highly organised and sophisticated crime rings.

This raises a question: could it be that the accounts harvested later are sold to fraudsters or money launderers? That their destiny is not decided at birth, but later in life? Or is it that both fraudsters and money launderers have the same level of professionalism and experience that makes their behaviour differ from genuine customers and therefore detectable? Regardless of the story behind it, the data shows one thing clearly. As an industry, we are dealing with highly organised and sophisticated crime rings.

A Behavioural Lens Enhances Transaction Monitoring and Account Opening

The next logical question: If behavioural biometrics can be used so effectively to detecting money launderers before they transact, could we also use it when they are already active? Not surprisingly, the answer is yes.

When fraudsters enter and authorise transactions, their behaviour differs from that of genuine customers. Thus, the amount of data to detect them is increased. With this, we can detect money launderers that go unnoticed by transaction monitoring systems. Of course, they would have ultimately been detected, but then lots of additional damage would have been done.

Two principles apply here: the more information, the better your decision can be, and the more different angles used, the more precise and robust the decision can be.

Next, we come to the account opening process which differs by bank. But regardless of the process, fraudsters know how to get past it. To understand this, we have to realise that there are different types of money launders and money mules. See the box below.

Different types of Money Launderers and Mules

The 100% bad – 40-60%

Opens account for malicious reasons. Does whatever to get the job done. Know what to answer to proceed smoothly through the CDD process. Starts fake businesses if need be. Steals, buys, phishes customer credentials. Etc. etc.

The good gone bad – 30-50%

Opens an account with his own credentials, at the moment of opening often for legitimate reasons. Then experiences financial hardship. Is offered a job over the internet, emails, social media. Foreign student selling their account when returning home. Romance scam, etc. etc.

The compromised ~10%

Used as temporary destination to extract stolen funds (money mule), or forward money to be laundered (money launderer). Compromised account or mostly used for fraud as they are quickly detected. The resulting trail is not something money launderers like, except when the funds are moved out of sight shortly after, like moved to a more favourable foreign jurisdiction.

The “100% bad” guys can be detected with high accuracy using behavioural detection, and many banks and financial institutions are already doing so. Still, some might be able to slip through. The accounts opened genuinely cannot be detected at all. This means that in order to prevent these malicious accounts from transacting, it is paramount that detection occurs within the forgotten gap – once again, after account opening and before the first transaction in done.

Preventing Fraud and Money Laundering Can Add Up to Huge Savings

The common saying “The sooner the better” so aptly describes how we must approach AML. This is all too true for both fraud and money laundering. If we proactively prevent fraud, we improve customer satisfaction by lowering fraud levels and save in operational costs as less alerts and cases must be handled. By proactively preventing money laundering, there are additional savings as there is less documentation to do, less reporting to the FIU, and lower regulatory risks. Finally, a bank with considerably lower fraud and money laundering levels will be perceived as a safer and more reliable bank. In the end, it all comes down to trust.