Every day millions of people are faced with the decision to buy, sell, or hold on to various items and assets. For example, due to certain shortages and market demand, the price of used cars has gone through the roof. You may be tempted to sell your daily driver or second vehicle to make an easy buck. You may also be thinking the recent crypto crash is a good time to finally buy in at a cheap rate. Or maybe you’re that person that constantly battles the urge to buy and sell more collectibles. Regardless of where you fall, these decisions aren’t always easy and can cause fear, uncertainty and doubt (FUD). However, once a decision has been made, the process of completing a deal or transaction has gotten easier over the years with access to technology like Facebook marketplace, eBay, investing apps, and online banking. According to Statista.com, there are 263 million digital buyers in the United States alone.

This surge of digital innovation has supplied an unmeasurable number of benefits to businesses and consumers. But unfortunately, those same technologies can increase the temptation to make a fast, easy, and very illegal payday. This leads us to the next money mule persona we’re breaking down, the Peddler.

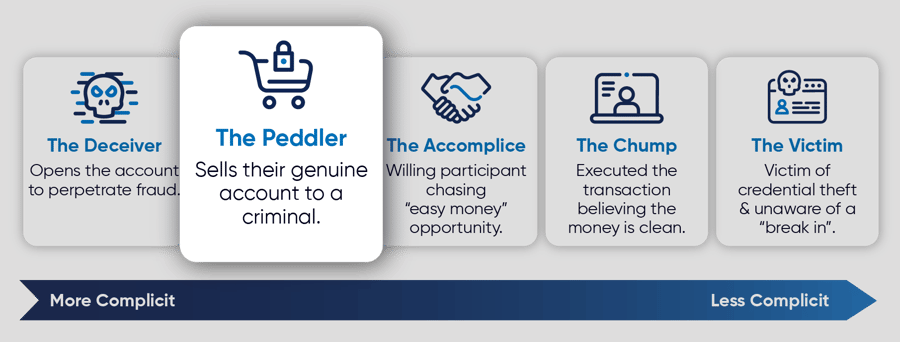

When thinking about the problem of money mules, there are different personas and use cases associated with a mule transaction. The Peddler is one of those personas and falls just after the Deceiver on the complicit scale. The Peddler is someone who sells their genuine account or multiple accounts to a criminal. During the height of the pandemic, the Peddler use case increased significantly, especially among young adults looking to make quick money. For example, some banks reported incidents where foreign exchange students, unaware of when they would be able to return back to college, sold their bank accounts to criminals.

Whether done out of malice, ignorance or desperation, the intention does not matter. Once a transaction is made, the Peddler has broken the law, even if it’s a one-time transaction and they are unaware of future illegal activity. Not only is it illegal to buy or sell an account, loaning an account to someone is a breach of bank and financial institution guidelines, and both parties could be subject to penalties and potential legal action.

Law enforcement agencies, such as the U.S. Department of Justice and Europol, have formed task forces in recent years in an attempt to disrupt mule networks worldwide. The Money Mule Initiative in the U.S. has been around for four years and has taken action in all 50 states. According to Arun Rao, Deputy Assistant District Attorney in the Justice Department, “While we don’t know exactly how much money has moved through money mules, a conservative estimate places that in the billions. And again, this is a nationwide problem.” The European Money Mule Action initiative, an international effort led by Europol, led to more than 1,800 arrests and the identification of over 18,000 money mules in only a three month period last year.

Let’s now look back at the decision to buy, sell or hold. One might think that something like a bank account would clearly fall in the “hold” category, but unfortunately that’s not always the case. Bank accounts and genuine user information are often bought and sold on digital black markets like a regular commodity. The transaction of selling a genuine account could be very lucrative for Peddlers and problematic for banks and financial institutions. Once criminals obtain the account, they may be able to fly under the radar for a while conducting money laundering activities. Until technology, or law enforcement, catches up with them.

To learn more about current trends in mule activity and how some financial institutions are responding, download the Aite-Novarica research report, The Emerging Case for Proactive Mule Detection.

This is the second blog in a five-part series on mule personas. Check out the first blog in our series, Deceiving the Deceiver: Stopping Mules at Account Opening.