Now that UK legislation has mandated APP scam reimbursement for the Faster Payments Service (FPS), questions remain for the Payment Systems Regulator (PSR) to define what might actually not be covered. The PSR recently published two consultancy requests to solicit feedback on these outstanding questions. The first consultancy is for Excess and Maximum Reimbursement Level for Faster Payments and CHAPS. The second consultancy is for the Consumer Standard of Caution. Since the Bank of England has recently agreed to work toward scam reimbursement for consumer CHAPS transactions (CHAPS transactions are same day ACH), this consultancy includes questions to address them.

From these documents, several key questions need to be addressed:

- What will the Maximum Amount of Reimbursement be?

- What will be the Excess Amount (amount excluded from reimbursement)?

- What will be the expected level of caution required by the consumer to be eligible for reimbursement?

- How will vulnerable consumer victims be treated?

- What if a consumer is scammed more than once?

Let's examine each of these questions in more detail.

Maximum Amount of Reimbursement

On the question of Maximum Amount of Reimbursement, the PSR proposes an amount of £415,000 per event. This matches the current maximum limit by the UK Ombudsman Service and would cover 99.98% of scam transactions by volume, but maybe only 95.5% of the value of the scams1. There would be a large number of romance scams and investment scams, well over the proposed £415,000 maximum, that would then only be partially covered. And these larger value scams are growing.

It is an open question if vulnerable customers would have a cap on reimbursement. The PSR states, “We are not proposing that PSPs must use the maximum reimbursement level we set. PSPs will be free to increase the level or remove it entirely for their customers.” But PSPs cannot reduce the maximum reimbursement level. According to the PSR, the maximum reimbursement level limits PSPs from unlimited liability for scams.

Excess Amount

Regarding the Excess Amount per scam transaction (or the amount excluded from reimbursement), the PSR clearly states limitations will not be applicable to vulnerable customers. However, the PSR does note that “in assessing vulnerability, PSPs should consider both the circumstances giving rise to the fraud and the financial impact on the victim.” So, this starts to infer there is a soft definition for “vulnerable customer.”

The PSR identifies three criteria for setting an Excess Amount as follows:

- Incentivizing customer caution

- Ease of understanding for consumers

- Minimizing financial loss for consumers

The PSR also provided three ways to calculate the Excess Amount.

- Fixed amount. There would be no reimbursement for this amount (e.g., a £500 scam loss with a £50 fixed amount for the Excess Amount would mean only £450 would be reimbursed).

- Percentage of scam loss. The Excess Amount would be a percentage of total scam loss. The absolute amount of exclusion on a large scam loss would be noticeable (e.g., a 10% Excess Amount on a £500,000 scam would be £50,000 not covered).

- Percentage of scam loss with a cap. This would be better for the consumer on large losses.

Another option to consider is the Excess Amount could be a fixed amount up to £X loss and a percent of the loss over £X.

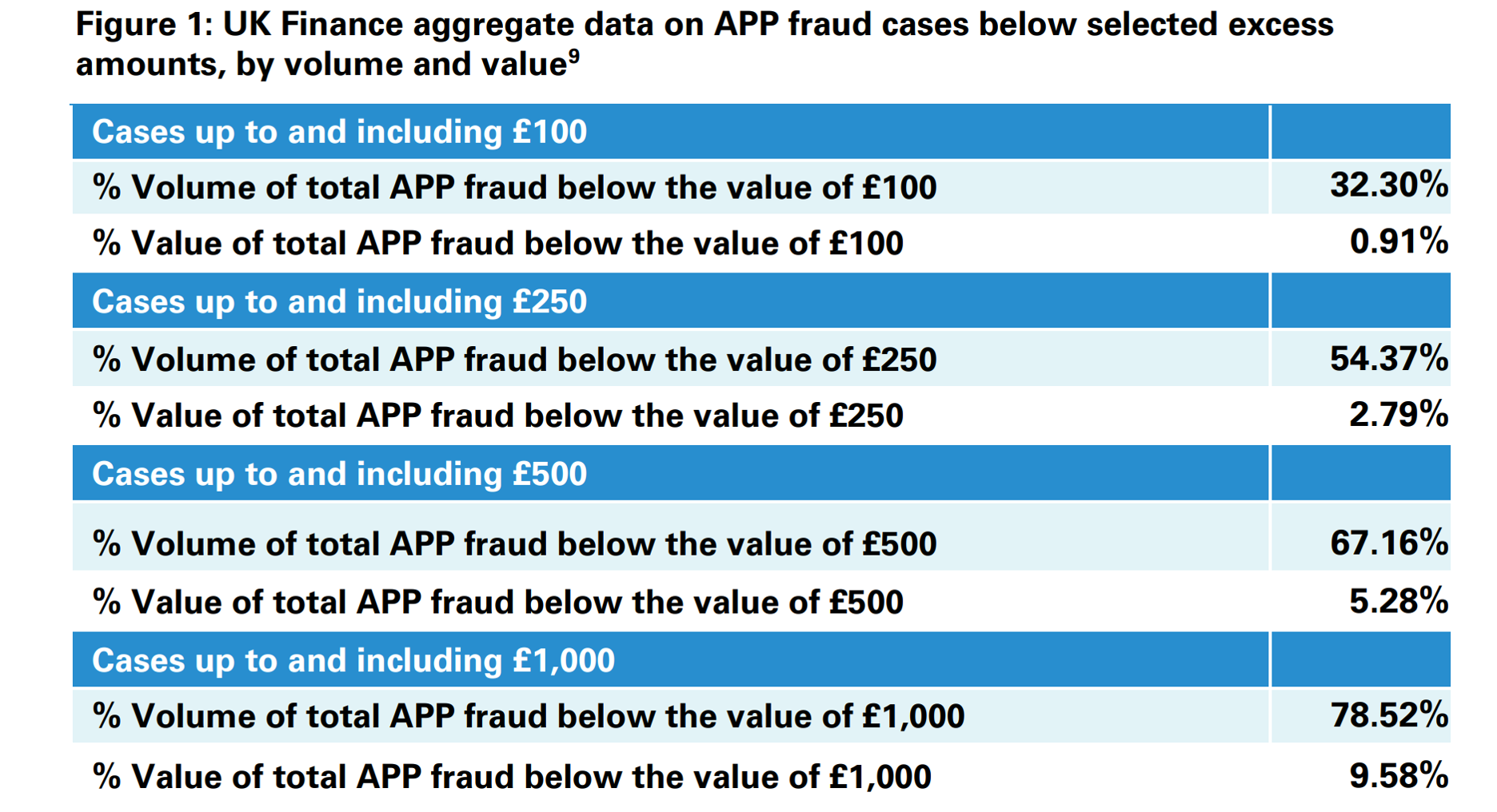

So, obviously, the higher the Excess Amount (TBD), the less that is reimbursed. The Excess Amount can act like an informal minimum. See Figure 1 from the PSR consultancy document showing number (volume) of scam transactions vs. the value of scam transactions.

Customer Standard of Caution

The second PSR consultancy document asked for comments on the customer standard of caution (care). There are two basic exceptions for the reimbursement requirement under this standard of caution:

- Customer commits first party fraud.

- Customer acted with gross negligence.

The PSR proposes a definition of gross negligence whereby the consumer must:

- Pay attention to ‘specific, directed scam warnings’ from the sending PSP. The warning by the PSP must make it clear that the intended recipient is likely a fraudster.

- Promptly warn the PSP about the scam transaction, but no later than 13 months after the last relevant payment was authorized.

- Must respond to reasonable requests for information by the PSP.

The burden of proof falls on the PSP to show gross negligence. Gross negligence is not applicable to vulnerable consumers.

Although the PSR requires the consumer to pay attention to these PSP warnings, the PSR creates a new exception by saying that “a consumer proceeding with a transaction despite these warnings should not automatically be deemed to be grossly negligent.” The degree of negligence should also consider these factors:

- The nature of the warnings provided by the PSP

- The complexity of the scam. This can be difficult to assess, in effect scoring each scam for complexity.

- Claims history from the consumer showing a ‘propensity to fall for similar types of scams’

- Whether the PSP had a chance to slow down/stop the transaction

These four items can generate a range of responses which then have to be considered in determining if gross negligence has occurred. And the complexity of the scam and the individual consumer claim history can really complicate this determination. Analysis has shown that once a consumer has fallen for one scam, they are more likely to fall for additional scams. The average victim will be scammed more than four times. Thus, claim history will become a common issue in assessing gross negligence. At some point, if the consumer has been scammed multiple times, will that alone be deemed gross negligence or not?

One thing the PSR has so far failed to address is what happens when the PSP invokes the Banking Protocol and brings a police officer to the branch to explain to the consumer the transaction is a possible fraud, and the consumer goes ahead with the transaction anyway. There have been nearly 50,000 Banking Protocol events since 2017. Not every one of these events was actual fraud. If it was fraud and the customer ignores the police and the branch staff, should this be gross negligence or not?

Closing Thoughts

The PSR considers that both sending and receiving PSPs and customers have a role to play in managing APP fraud risk. The PSR assumes that PSPs will have strong controls in place to prevent these types of scams. Reimbursement is the incentive for PSPs to provide these controls.

The PSR has really done a good job of documenting the journey to APP scam reimbursement. This final step, on the definitions surrounding the actual reimbursement calculations and what will be excluded from reimbursement, may be the most difficult. There are several key items that can be challenging, including 1) what will be the Excess Amount excluded from the reimbursement amount, 2) how should the PSR treat an unsuccessful Banking Protocol intervention (gross negligence or not), 3) how is gross negligence really defined, given the various examples above of what constitutes gross negligence, and 4) how do you define a vulnerable consumer, especially taking into account a customer who has fallen for multiple APP scams, how complex was the scam, what is the age of the victim, etc.? These four items will have a significant impact on the actual reimbursement. Plus, any maximum amount chosen will leave a good percentage of high value romance and investment scams uncovered.

But this, and more, is why the PSR has wisely initiated this consultancy to get input from the PSPs, consumers, The Ombudsman Service and consumer advocates (such as Which?). This is a very important step.