When banks think of transaction authentication, they look at obtaining confirmation from the customer through an alternate channel. For example, if a customer wants to pay someone through internet or mobile banking, banks send a one-time passcode (OTP) to a registered mobile number or email belonging to the customer as an extra layer of security to verify it was the genuine customer who initiated the transaction. Some banks will include the transaction amount and name of the payee/beneficiary/merchant so that the customer knows how much will be debited once they enter the OTP.

For even further assurance, some banks may ask the customer to answer predetermined security questions or input random numbers printed on the back of a debit or credit card.

While all the above controls would appear to be nearly resistant to fraud, there is an unseen gap. Their strength relies on the assumption that it is the genuine customer who has initiated the transaction, and it is the customer who is receiving and entering the OTP, entering the grid numbers, or answering the security questions.

A typical transaction authentication process does not determine whether the information being entered – the OTP, Card Grid Value, answers to security questions – is being provided by the genuine customer. Perhaps it is a fraudster who has tricked the customer into sharing the information. Simply knowing the information is not enough because these types of information can be easily obtained from the genuine customer through phishing, malware, or other forms of social engineering.

Those of you who have ever visited a bank branch to request a transaction know that bank staff ask you to show your original ID to ensure the photo and signature match before processing your transaction. In the digital world, user id/password, OTP, grid value and security questions have replaced the ID card and signature verification. Anyone who knows this information can take control of an account.

Payment Security Starts at Onboarding

Even before transaction-level risk, we must take a step back to where the first point of vulnerability begins – the onboarding process. This is where we look at account-level risk and ask the question: Is this a genuine account or a mule account? Let’s look at some scenarios where an account may be opened and then operated to route fraudulent payments.

- The account is opened by a real person with real documents, and then it has been handed over to someone else for operating. These are mule accounts opened with the sole purpose to do money laundering and/or route proceeds of fraud. In few cases, the real account holder may be complicit in the crime, selling the use of their “good name” to move illicit funds in exchange for a percentage of the transaction value.

- The account is opened by an impersonator using the documents of a real person, without their knowledge or consent, and operated by fraudsters for "Business as Usual" activities. In such cases, document verification checks are passed, even though the person using those documents is not the genuine customer.

- The account is opened by a real person who is using it for legitimate personal or business activities. However, fraudsters have been able to gain control of the account, either through phishing, malware or social engineering and use the account to move funds or convince the genuine customer to move the funds on their behalf. In such cases, all the information which is used by banks to authenticate the transaction is compromised on the customer’s end.

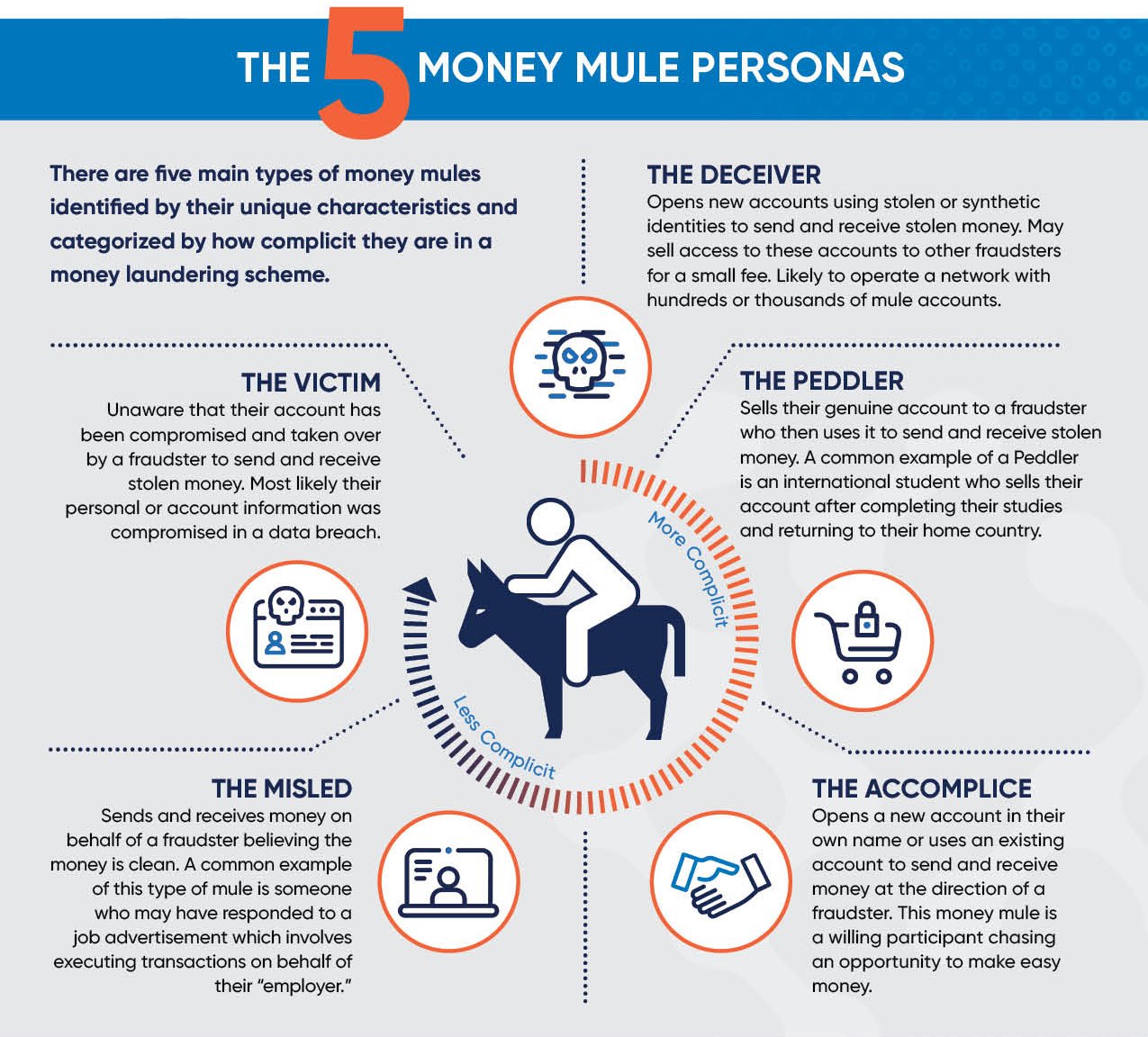

The image below shows the different types of money mule personas.

Unless we explicitly know that a transaction is initiated from a known fraudulent device or money is being sent to a known fraudulent account, the problem with most legacy transaction authentication controls is they assume the person providing the information (OTP, grid card value, etc.) to authorize a payment is the legitimate account holder. And they also do little to address cases where a mule account is at work. This is why it is so important for banks to do more to secure the customer onboarding process.

Regulators are also taking notice. For example, the Reserve Bank of India, Indian Central Bank, recognizing the role money mules contribute to the fraud problem, recently updated the Master Direction on KYC and made amendments to Customer Due Diligence (CDD) processes.

Four Controls for Better Payment Security

Here are four recommended controls I believe are critical to payment security, and it starts at onboarding:

1. Implement stronger controls at onboarding to ensure the person whose information or documents are being used to open the account is the legitimate account holder. This entails:

- Capturing document copies by asking the customer to show original documents

- Getting a video selfie while ensuring deepfakes are not allowed and recordings are not used

- Registering the mobile device. The ideal journey should start from the mobile channel rather than the web channel.

- Capturing behavioural biometrics and how the person interacts with their device

- Capturing physical biometrics, including voice

2. Any new device registration follows the same process as above.

3. Leverage behavioural intelligence to look for signs of activity from bots, malware, or remote access tools at login and throughout the session. This can be determined by looking at parameters such as touch or swipe interactions, device movement, and navigation patterns.

4. Leverage transactional and behavioural data to look for signs of mule account activity. Research shows that four out of five mule accounts are highly active 90 days prior to an incoming payment. For example, prolonged periods of latency followed by a sudden spike in activity (e.g. multiple daily logins) is a behaviour commonly found in mule accounts.